Ocean Circulation

Ocean currents work like giant conveyor belts, moving warm and cold water around the planet.

- Surface currents are pushed mainly by winds and steered by Earth's rotation.

- Deep currents form when cold, salty water sinks and spreads through the deep ocean.

- Warm currents like the Gulf Stream carry heat toward colder regions.

- Cool currents like the California Current bring nutrient-rich water that supports fisheries.

Drivers of Ocean Circulation

Several forces combine to keep this global conveyor belt moving:

- Wind-driven circulation: Winds push surface waters, creating gyres and steering currents across ocean basins.

- Thermohaline circulation: Differences in temperature (thermo) and salinity (haline) control water density, driving deep currents.

- Earth's rotation (Coriolis effect): Deflects currents, shaping their paths into spirals and gyres.

- Tidal forces: The gravitational pull of the moon and sun stirs coastal and deep waters.

- Heat exchange with the atmosphere: Ocean waters absorb and release heat, influencing density and circulation strength.

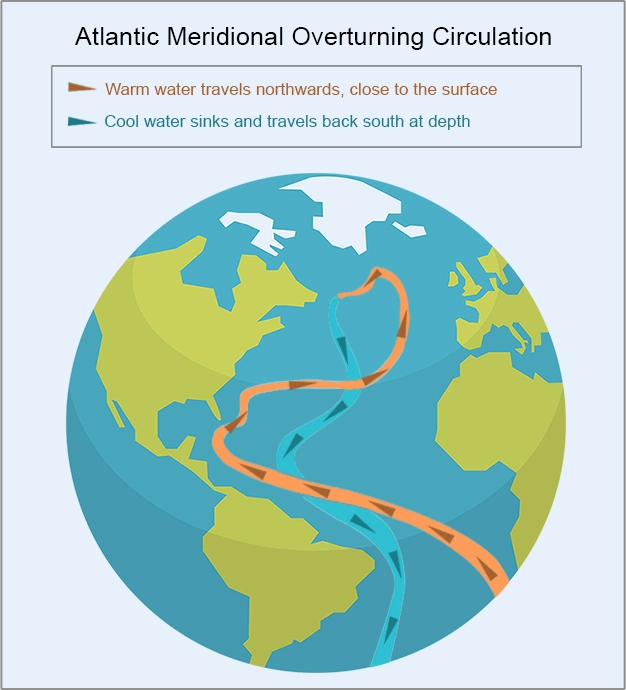

The AMOC: A Global Heat Engine

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is one of the most important systems formed by the collective action of currents.

- It begins with the Gulf Stream, which carries warm, salty water northward.

- As this water reaches the North Atlantic, it cools and becomes denser, sinking into the deep ocean.

- This sinking drives a return flow of cold, deep water southward, completing a massive loop that connects surface and deep currents.

- The AMOC acts like a climate regulator, transporting heat from the tropics to higher latitudes, which helps keep Europe relatively mild compared to other regions at similar latitudes.

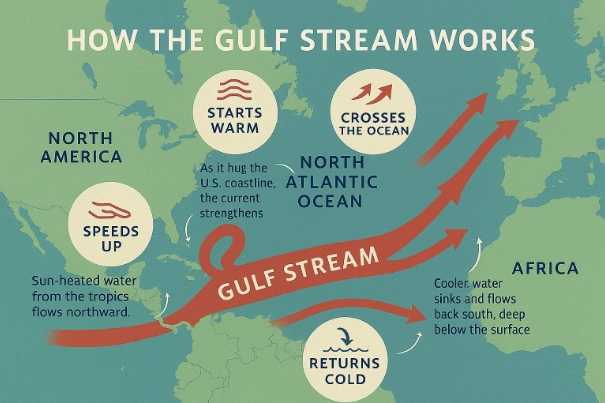

The Gulf Stream: Nature's Ocean Conveyor Belt

The Gulf Stream is a powerful ocean current that carries warm water from the Gulf of Mexico up the east coast of North America, then across the Atlantic toward Europe. It’s like a giant river in the sea, moving heat around the planet.

- Starts warm: Sun-heated water from the tropics flows northward.

- Speeds up: As it hugs the U.S. coastline, the current strengthens.

- Crosses the ocean: It heads toward Europe, warming nearby countries.

- Returns cold: Cooler water sinks and flows back south, deep below the surface.

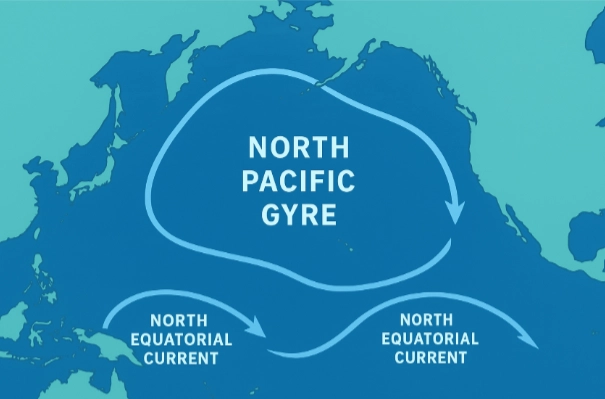

The North Pacific Gyre: A Vast Oceanic Engine

The North Pacific Gyre is one of the largest circulation systems on Earth, formed by the

collective action of four major currents.

- It begins with the Kuroshio Current, which carries warm water northward along the coast of Japan.

- This water then flows eastward across the Pacific as the North Pacific Current.

- It then turns southward as the cold California Current along the western coast of North America.

- Finally, the North Equatorial Current closes the loop, moving westward near the equator back toward Asia.

Together, these currents create a massive clockwise circulation that redistributes nutrients, shapes ecosystems, and traps floating debris. Unlike the AMOC, which connects surface and deep waters through sinking, the North Pacific Gyre is primarily a surface circulation system, acting as a climate stabilizer and ecological driver across the Pacific basin. It fuels rich upwelling zones along its eastern boundary, supports one of the most productive marine ecosystems in the world, and is also the site of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a stark reminder of human impact on ocean systems.

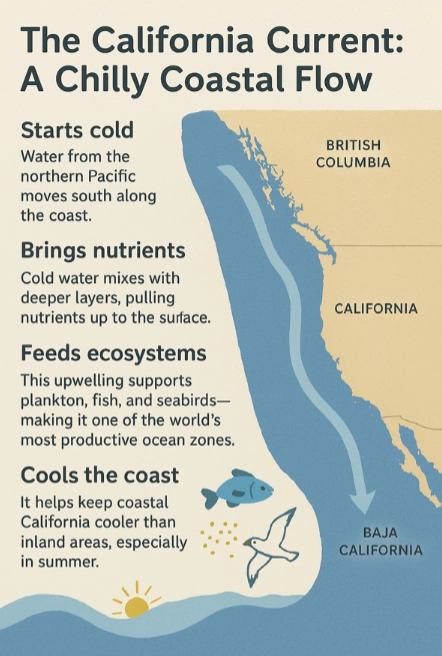

The California Current: A Chilly Coastal Flow

The California Current is a cold ocean current that flows southward along the western coast of North America—from British Columbia down to Baja California. It’s part of a larger system that helps cool the coast and support rich marine life.

- Starts cold: Water from the northern Pacific moves south along the coast.

- Brings nutrients: Cold water mixes with deeper layers, pulling nutrients up to the surface.

- Feeds ecosystems: This upwelling supports plankton, fish, and seabirds—making it one of the world’s most productive ocean zones.

- Cools the coast: It helps keep coastal California cooler than inland areas, especially in summer.

Extending Ocean Circulation: ENSO as a Disruptive Force

The El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a natural climate cycle that alters the balance of ocean circulation, especially in the tropical Pacific. It has two opposing phases:

- El Niño: Weakening or reversal of trade winds causes warm surface water to pile up in the eastern Pacific.

- La Niña: Strengthened trade winds push warm water westward, enhancing cold water upwelling in the east.

The Physics Behind ENSO

- Wind-driven changes: Normally, easterly trade winds push warm surface water westward. During El Niño, these winds weaken or reverse, allowing warm water to spread eastward.

- Thermocline tilt: The thermocline (boundary between warm surface water and cold deep water) flattens during El Niño, suppressing upwelling. In La Niña, it steepens, intensifying upwelling.

- Heat redistribution: El Niño shifts heat from the western to the eastern Pacific, altering pressure gradients and jet stream patterns.

- Feedback loops: Warm water enhances convection and rainfall, which further weakens trade winds—amplifying El Niño. La Niña strengthens the Walker Circulation, reinforcing trade winds and cooling.

Ocean Impacts

- El Niño:

- Suppresses nutrient-rich upwelling off South America, leading to fishery collapses.

- Warms surface waters, disrupting coral reefs and marine food webs.

- Alters current strength and direction, affecting global thermohaline circulation.

- La Niña:

- Enhances upwelling and productivity in the eastern Pacific.

- Intensifies ocean stratification in the western Pacific.

- Can strengthen the Pacific gyres and influence deep water formation indirectly.

Human and Climate Consequences

- El Niño:

- Brings floods to Peru, droughts to Australia and Indonesia, and milder winters in North America.

- Increases global average temperatures due to widespread ocean warming.

- Disrupts agriculture, water supply, and disaster preparedness worldwide.

- La Niña:

- Triggers stronger Atlantic hurricanes, cold winters in Canada and the northern U.S., and floods in Southeast Asia.

- Can temporarily cool global temperatures, counteracting warming trends.

- Impacts crop yields, wildfire risks, and energy demand.